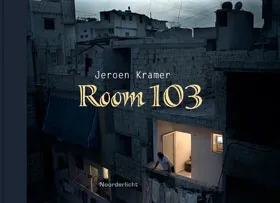

103 is just a number. It also happened to be the number of Jeroen Kramer’s hotel room where he lived while working as a photojournalist in Baghdad during the war – and became his subsequent nickname (the hotel staff had trouble pronouncing his Dutch name). In the naming of this book Kramer perhaps also sees himself as “just a number” and the work he was creating as perpetuating that notion – by being just another photojournalist in a war zone, shooting photographs of just another soldier or civilian senselessly killed. What Room 103 isn’t, is a book claiming to be about war and conflict – one that neither shows nor tells you anything new. While most books created under the guise of “worthy photojournalism” intentionally separate the author from the work – and end up creating the opposite effect – Kramer’s is the reverse in the blatant use of the personal. This book is about what it really means to be present in conflict, what it means to have to run, against all natural impulses, towards gunfire. The photographs contained in Room 103 mark Kramer’s time living in Beirut, Baghdad and Damascus. The collage of written stories – accounts of personal friendships and hardships – are fragmentary and disjointed, perhaps a reflection on the reality of war. Kramer is not trying to make sense of war, an entirely impossible feat anyway, and the photographs reflect this. The series of 12 images that bookend the work, presented as a strip inside the front and back covers, tell the story of a convoy attacked en route to Mosul in which four soldiers were killed. Graphic and tense, these are the most predictable images in the book – or rather outside it – while those within are the more lyrical and quietly suggestive. The images here are secondary to the text yet not illustrative. After reading the story of Khaled, a close acquaintance from Damascus, you find yourself searching for a photograph of him – along with the others mentioned in the stories – but there aren’t any. And, perhaps they don’t exist – the images or the people in Kramer’s stories.

Room 103 winner of the dutch doc award in 2010

The ones that do feature are those of daily life – weddings, children playing, street scenes at night – with images of horror thrown in – mass graves, bloodied faces and dead bodies. Although at first glance appearing to be devoid of context, a list of captions does appear at the back, telling us simply, where, when and what. There is an overriding sense that Kramer spent time with the people pictured and actually got to know them before taking their photograph. In one story, “Ammar is Sick” he explains how, during drinking sessions with his group of Iraqi friends – something, now that the country is “democratic” and “free”, they have to go to Jordan to indulge in – there is a predictable chain of events: first singing and merriment and then the inevitable sobbing: for family, for country, for the present situation. The scene becomes one that no photograph could communicate.

Kramer’s real intentions with this book become apparent at the end, when he writes of the email sent to his editor, talking of his self-loathing – the only reason he can come up with as to why he does what he does. Being a photojournalist is, to him, a suitable punishment for compassion fatigue and compliance in a media machine that simplifies and desensitises. He likens the experience of photographing one man, shot through his windscreen and nearly dead, as useless for him because there is no caption information to include with the image. The man becomes for him, along with countless others, a Dorian Gray, suspended in this stasis of being.

Room 103 may be overcomplicated by its fussy design and odd coloured pages. And its awkward format, perhaps trying to emulate a scrapbook, could have benefited from being either larger or smaller. But its strength as an incongruous mix of word, image and emotion emerges after being immersed in the personal stories of love and death. While Kramer may only see himself as perpetuating a cycle of exploitation, this book represents his obligation to reverse the trend, to make sure that the people with whom he is interacting and whose stories he is telling, do not become just another number.

Lauren Heinz